Light As Shadow: The Value Of Natural Light In The Legacy Architecture of Japan

The world is a different place in the dark and all the shades and nuances in between shape and sculpt a space like a potter at a wheel. From a fluorescently lit takeaway to a warmly lit jazz bar in the evening, the different emotions that lighting can elicit is a vital ingredient to create that space. It has been said of light, that it is the soul of architecture (Plummer, 1992), light not only allows us to see – through its obvious functional application – but the way light performs in a space changes our way of being in that space; shifting our quality of presence.

“Space and light and order. Those are the things that [people] need just as much as they need bread or a place to sleep”

— Le Corbusier

‘In Praise Of Shadows’ (1933), an influential essay by Japanese novelist Jun’ichirō Tanizaki is a sprawling love letter to the Japanese aesthetic he grew up with to what he claims is all birthed from their relationship to natural light. Tanizaki compares combatively Japanese design with the west’s, defending the subtle and tranquil principles of Japan with what he claims is the brash and overtly bold movements of European design, something which Tanizaki feared prophetically during the writing of this essay in 1933 would come to pollute and corrupt Japan design as it had done throughout Europe. But how do these principles of natural light come about in the first place? What are (or were) the philosophies which guided these design decisions and where were they derived? Let’s find out.

“In Japanese Architecture the distinction between outdoors and indoors is very vague” mulls architect, Toyo Ito in the documentary Kochuu (2010), blending what is considered from a western perspective as nature (outside) with shelter (inside) as one continuous aspect of the same character. Echoing this, architecture critic Chris Giles puts succinctly, “In Japanese thinking, there is no built or natural environment — just nature”, making architecture and nature not combative but flowing together as a singular force – the building is not an imposition on nature or even a dialogue with it but one and the same voice.

Many working architects today contend this focus on nature is born from Buddhist and Shinto beliefs – Shintoists make up 69% of Japan’s population and Buddhists hold on to 66.7% (Statista, 2018). As with most cultures, the dominant religious underpinnings act as the blueprint and set the direction of the culture for generations. Shintoism is the indigenous religion of Japan, it’s polytheistic and animistic, believing in the spirit of every possible thing and with multiple deities of worship. Its prominence emerges from an agricultural society in the Yayoi period (300 BCE–300 CE) where environmental changes had an almost immediate effect on the misfortunes and fortunes of villagers. For Shintoists, good and evil are synonymous with growth and decay; where there is good fertile ground and good weather, there is abundant crop growth and a theoretically thriving society on top. Broadly speaking, Shintoism promotes harmony, connection, and a respect for the natural world, in Shintoism, nature is first, as it is seen as the all-pervading power we rely on – the growth and decay of a society are dependent on this reverence of the natural world which they believe to be appeased by their own actions in accordance with spiritual allegories.

“Connection to nature has always been an important feature of Japanese architecture. This can be attributed to Japan’s Shinto and Buddhist beliefs, which have had a significant influence on its architecture. This can be clearly seen in the focus on natural light and the use of raw wood as a building material, both on the exterior and in the interior.”

— Architecture & Design, 2020

Even though Japan is now a flourishing first world country defined by technology, science, and capitalist drive, their dominant religious culture is a paganistic polytheism that celebrates life and fertility – being the union of what’s seen as the male forces of the heavens (rain) and the female forces of the earth (creation). Whereas in the west, polytheistic religions such as Druidry or Hellenism have long been relegated to outsider religions by the influence of monotheistic practices such as Christianity and Judaism which put less emphasis on the natural world and more emphasis on the internal measuring of an individual’s ethics and actions to others. Yet Shintoism is so influential in Japan, even as a visual language, images of Shintoism are wholly nationalistic – you can’t imagine a travel agent promoting trips to Japan without a ‘Torri’ gates and the compulsory backdrop of a misty mount Fuji.

Originally an import from India, Buddhism made its way to Japan from Korea and China and is now the other predominant religious influence of Japan. For many Japanese, Shinto and Buddhism complement each other and have realised a hybridisation of the two. One clean crossover is the significance of nature. Buddhism is very much concerned with how to live a happy life and according to Buddhism, people cannot live separated from nature and be contented. From this, many questions begin to form on how to live a life in harmony with this nature and how to do so architecturally come into play.

The Japanese teahouse or ‘chashitsu’ is a good place to start looking at how they answer these questions of living in harmony with nature. The teahouse during the Edo period expresses a principle called kochuu which literally means ‘in-the-jar’. Kochuu is an attempt to create the nature of the universe in a small enclosed space, a space where principles of Shintoism (reverence for the natural world) and conscious practises of Buddhism (stillness, contemplation, meditation) could be practised, a place which seminal architect Kisho Kurokawa states, “where your thoughts were on the universe”.

In Japanese architecture, small spaces could be filled with big thought and so the Japanese house or garden need not be sizable to express a sense of profundity and depth – mountains and rivers for example are expressed creatively and spiritually, not with water, but with stones and sand. This, they claim, is more spiritually enriching and highlights the contemplative nature of this culture – the contemplation of which is dependent on stilling the inputs of the thinking mind so that we are able to observe presently the pause of ripples on water or the trembled opening of a pink lotus – the universe is to be found in the gaps of these happenings and it is in the gaps where conclusive meaning is to be realised – the Edo teahouse, therefore, is the de-facto temple of contemplation on nature, a place to stretch those gaps and live inside them for a little while longer – a withdrawal from everyday life, your own little heaven.

Most if not all traditional architecture of Japan is in some way reflective of these ideas on nature, but what does this mean with their approach to light? Light can be elusive, as invisible and as easily ignored as the principles of these philosophies. For traditional Japanese architecture, the use of light is equally about shadows, a lot like the way the distinction between outdoors and indoors is vague, the distinction between light and shadow is additionally nebulous – the light, and the lack of it, is interconnected and one. Again, what is echoed is a non-dualistic approach to nature whereas what is ubiquitous in European thought, from Kant to Descartes, is a consistent notion of dualism where opposites exist everywhere including architecture, as if nature and architecture are in constant combat with each other, thus in building anything, nature is conquered. In Japanese architecture, however, the space between these opposites is of greater importance and for them is the cure to dualistic, limited and finite thinking – again, the goal is to place one’s thoughts on the “universe”, on the infinite, on all the happenings and non-happenings at once.

Of course, some design decisions are purely functional. For example, geographically, Japan is frequented by rainfall and the material most available for building was wood. As a result, to keep the wood supports from rotting or becoming soft, the roofs had to entirely cover all the foundations with deep-set eaves, which invariably not only shelter rain but also natural light, allowing it to only enter the dwellings in those small openings of time when the sun was horizontal to the shelter. “The Japanese style of building in which the light slides in from the sides can be found nowhere else in the world but in Japan” (Fujimori, 2019). Because of this 90-degree cast light, you get consonant shadows projected onto everything, so to work with this, you have movable paper screens called shōji. Shōji works in diffusing the light by using a traditional paper called washi, creating a stable diffused light to softly illuminate a given space. This coexistence of high contrast shadows and the palely lit paper surface is intrinsic to Japanese architecture.

A contemporary home in Japan, still with the deep-set eaves despite better materials to withstand the weather.

“The Japanese house is subject to exceptional constraints, from earthquakes and typhoons to rains and floods […] their main concern is to integrate – in the narrowest sense of the term – the building into the site so that it engages in dialogue with the surrounding space”

— Roland Schweitzer

Jusansonoseki (Thirteen-window sitting room). Even with thirteen windows, the Japanese house is no better lit but look at those bokeh-like shadows which will move and flutter, animating across the floor telling a story of the day.

Again, using the teahouse as an exemplar of architectural principles, light in this setting was used with strict rules and conservation. Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591), the famed tea master of Japan, implored that the only light in the teahouse should be diffused light filtered through shōji. Because of this, shōji is used for walls, doors and ceilings to help diffuse shadows in the tightest of spaces of the chashitsu (teahouse). As a result, the tea ceremony is a complex symphony of light, shadow, and diffusion, weaving a tapestry of tightly contrasted shadows with bokeh-like diffusion and illumination. Light in the chashitsu is an almost living and breathing organism, the shōji projecting the interior with the site which surrounds it, placing any inhabitants back in union from where we can become so detached in our hustle and bustle exaggerations of daily life, back into the sublime indifference of nature.

The materials found in the Japanese house are equally important to the use of light. The wood in older buildings for example have zero finish. And not just for showing an appreciation for the nature that birthed it but allowing a rich smoky patina to form over time. The slowly darkening veins of the wood tells a story of antiquity and the building becomes like living with a wise master. Novelist Junichiro Tanizaki claims this patina is lost in the brilliance of high illumination – it requires a dimness to sit quietly and elegantly let you know its story.

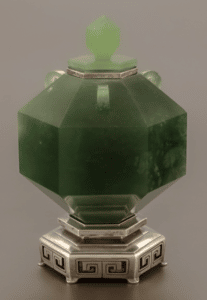

When wood is finished, it is particularly adored in black, brown, or deep red lacquer. Again, the glossy nature of this lacquer (or urushi) completely transforms under a brightly lit setting as compared to a dim and much-preferred shadow hung setting – this is why it is generally reserved for indoor use in furniture and tableware. Some lacquerware, such as the example of bowls below have the smallest of gold flecks from a technique called Maki-e. This technique accentuates the flickering and reflection of the ambience of a candlelit room; the rate of the dancing gold sparkles harmonising with the nighttime breeze that invariably finds its way through the wooden home. But this sort of reverie and repose for the place and the food in front of you is lost in the brightness of a midday sun or a fluorescently lit restaurant. The gold or silver subtlety is lost when compared with the abundant glare of shining golds, silvers, and bold white ceramics of European tableware. When there is gold, which there is in fact plenty of in Japanese design, it is generally polished to a matte finish to reduce this brilliance and increase the depth and is almost always used exclusively with a recessive black or dark urushi.

“Darkness is an indispensable element to the beauty of lacquerware”

— Junichiro Tanizaki

Jade is also a much well-loved material of Japan, in 2016 becoming their national stone. Tanizaki writes around 1910 of jade, “we (Japanese people) much prefer the impure varieties of crystal with opaque veins crossing their depths […] we do not dislike everything that shines, but we do prefer a pensive lustre to a shallow brilliance, a murky light that, whether a stone or an artefact bespeaks a sheen of antiquity”. Again, it is the way light plays on these elements, and it is better played with when the light is kept in its relationship with shadow – where light can truly be seen and prayed on. One can understand this better when compared with the crystalline purity of western design features of a similar time period.

What has been laid out, experimented with and compounded into the culture by a society is what the children of that culture are left with to play with well into the future, and though this may ultimately change direction and evolve – and sometimes beyond recognition – our ways of seeing and thinking remain embedded in the bones of the past. The divergent ways of seeing and thinking about light wildly differ from what was on offer around the same time in Europe than on the archipelago of Japan.

I found the religious or philosophical views on the natural world the biggest influence on this way of seeing light. Japan saw nature as an all-pervading force that is to be revered and respected, as a result, building on nature should complement the site where it sits – to become a part of it. Whereas, in European territories – prior to modernism – the building is seen as human ingenuity and is itself a monument to human intellect and conquering nature – an argument highlighted further in a cynical/postmodern frame in the brutalist movement of the 20th century where they purposefully emphasise this in order to expose. It’s out of differences like this that light takes a different form.

Wotruba Church, Vienna via Flickr

Other key elements were geography and prevalent material, and even though the European continent has a much wider variety in climate the difference among styles of the 16th to 18th centuries were only iterative across the continent. Japan on the other hand, though initially influenced by China, came into a wholly nationalistic style all their own during the Edo period and developed wide set eaves to offset rain from the wood foundations – this invariably affected light in the interior.

When we get inside to the materials that furnished the dwellings, they additionally accentuate natural light in other disparate ways worth noting. In both areas, for example, there is a distinct use of gold as a rare and valuable element, however, it is applied in ways that again reflect the foundational philosophies which guide their cultures. In Japan, though it is indeed recognised as a scarce and valuable material and one that is associated with status, it is also applied in a shadowy or darkly lit setting. Even if applied in abundance to a vase or similar, the vase will sit in a manner where light should discover it through its own nature. Compare this with Europe of a similar period, and it is simply the ‘bigger is better, more is more’ maxim.

Drawing-Room of Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

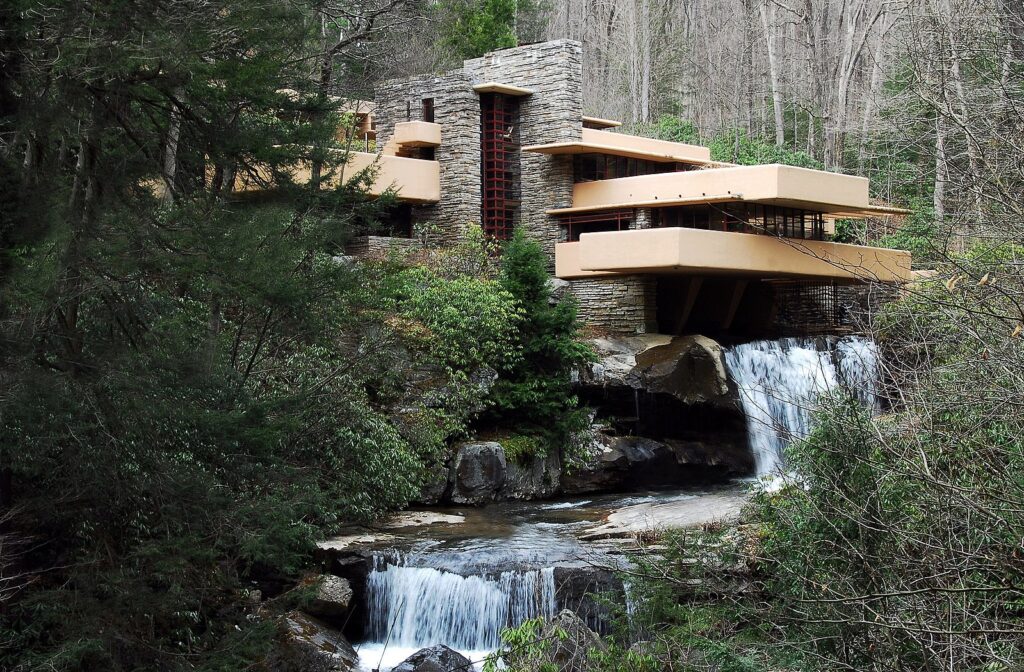

When we get to the modern period of the late 19th century into the 20th, we find a more industrial world with burgeoning globalisation where the west starts becoming influenced by further afield foreign cultures. This is when we start seeing the arts bringing in new influences into their work in a modernist reach for originality (Butler, 2010), such as Picasso’s 1907 work La Señoritas de Avignon featuring African mask forms in facial features or Gustav Mahler’s Das Lied Von der Erde (1908–1909), featuring text translated from Chinese Buddhist poetry. Modern architecture too around this time starts to be influenced by Japanese traditional design and influenced by similar philosophies of design put forward by architects like Frank Lloyd Wright in America with his Prairie Style – emphasising respect for the site to which the building presides which you can see fully comes to apex in 1935’s construction of the seminal Fallingwater.

“I think Wright learned the most important aspect of architecture, the treatment of space, from Japanese architecture. When I visited Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, I found that same sensibility of space. But there was the additional sounds of nature that appealed to me.”

Tadao Ando (1995 Laureate: Biography, 1995)

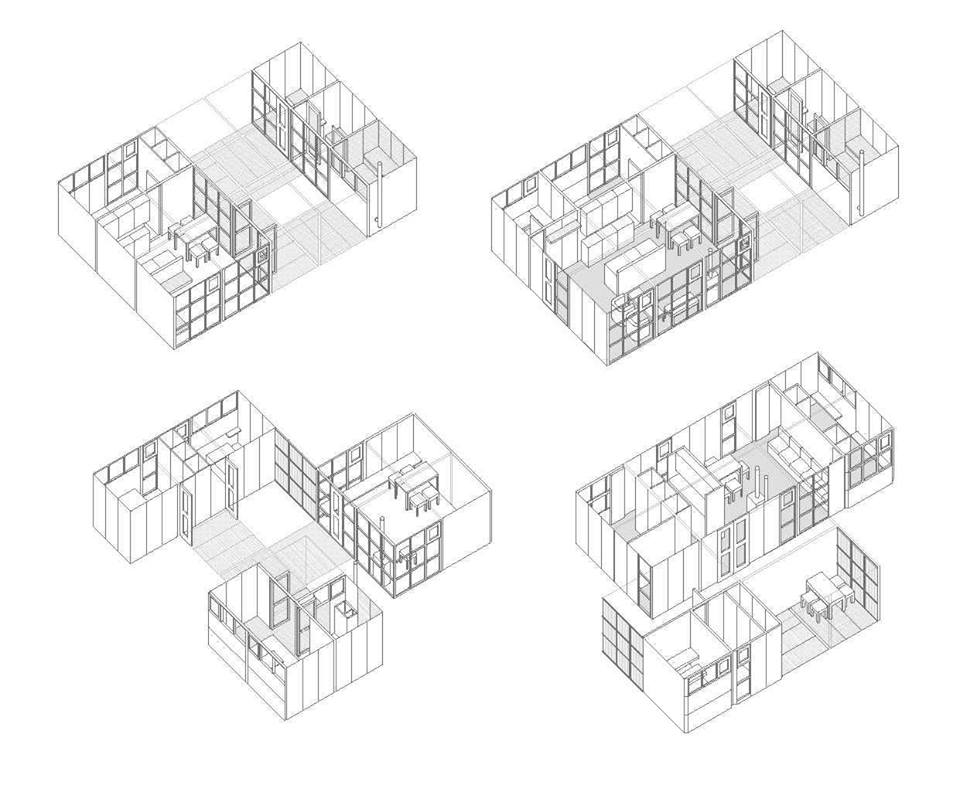

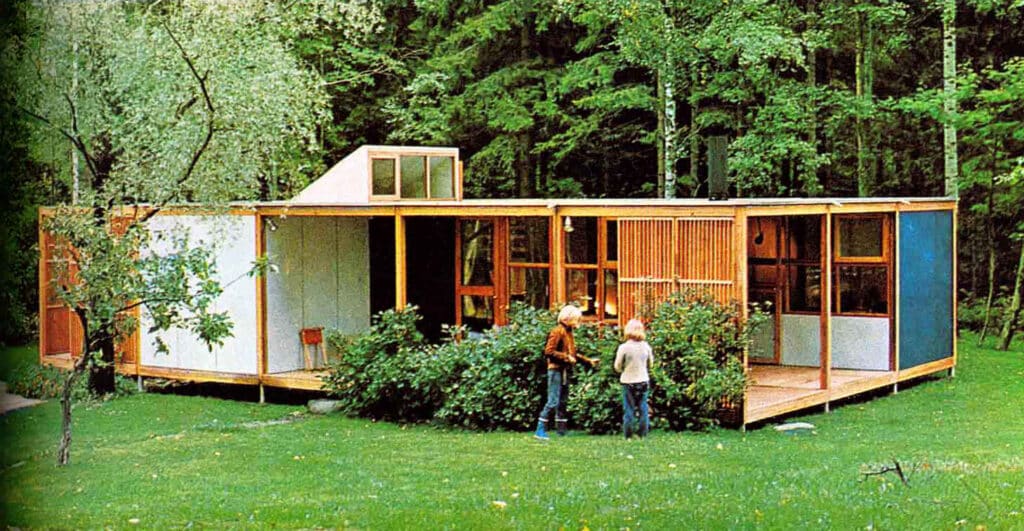

What becomes evident is that modern architecture matches naturally to the Japanese style when things fast start becoming more and more modular and rational as a product of industrialisation. As we zoom forward to the 1960s there becomes a full symbiosis of the two disciplines, European culture in particular realising, “In the ’60s, Japanese architecture was the object of much admiration […] Japanese aesthetics tally with the rational demands which emerged from industrialisation” — Juhani Pallasmaa

The Moduli System Project by Kristian Gullichsen and Juhani Pallasmaa via ArchitectureForThe99

Now, in the present, we live in a more globalised world than we ever have done before, communication and collaboration are possible without ever physically meeting, and as the worldwide COVID19 pandemic proved, every one of us, despite age and background, are willing to get on board with these sorts of virtual connections and make the world essentially a smaller place. My point is, in the past, you had parts of the world who were left to develop solely on their own, gestating solely over hundreds if not thousands of years while other pockets of the world had their own things cooking – oblivious to others. Things move faster now, our technology has ensured that and we can be grateful for much of the stuff it has brought us, but what if in our haste to be constantly entertained by connection and consumption we miss another new beautiful way to see?