08 Nov Visual Cues, Visual Culture, And The Ongoing Nostalgia Of The Simpsons

[vc_row css_animation="" row_type="row" use_row_as_full_screen_section="no" type="full_width" angled_section="no" text_align="left" background_image_as_pattern="without_pattern" el_class="blog-new-hagan" z_index=""][vc_column width="1/4"][/vc_column][vc_column width="1/2"][vc_column_text]We are by nature, pattern recognition machines.

Sometimes all we need is colour and composition and we can tell exactly what something is saying.

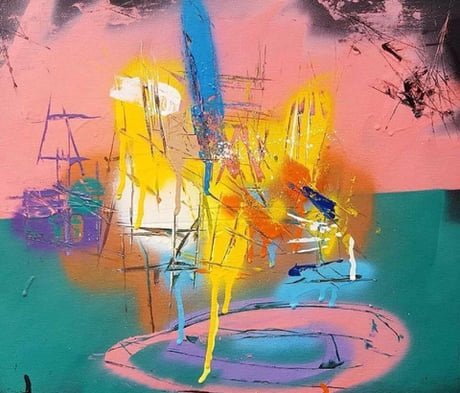

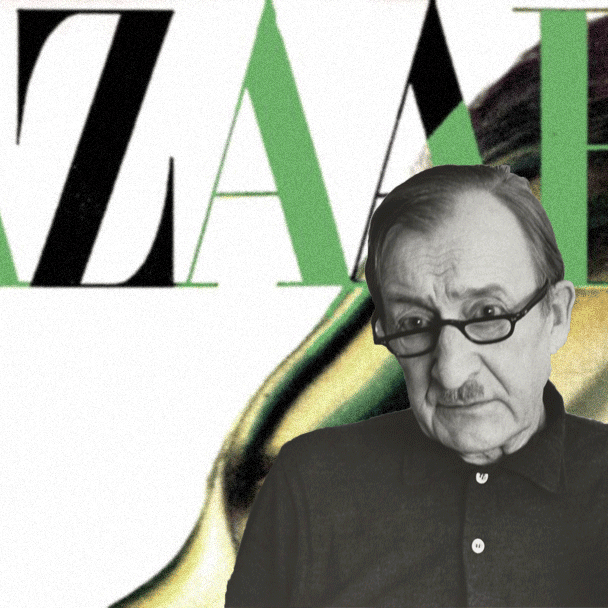

A friend recently sent me this with no words, no introduction, just this, an image sitting there in my message box with no explanation. But none were needed.

Here, all we need is three colours and a general composition and we understand in an instant what it's telling us. By presenting us an abstraction, our brains naturally try to 'solve' it, this makes us invest time and feel accomplished when we figure it out. It's similar to the success of Milton Glaser's 'I Love New York' graphic. By presenting you a letter, a symbol, and an abbreviation our brains decide it's a puzzle and a puzzle that's solved in an instant. It's satisfying.