Can Computers Be Creative?

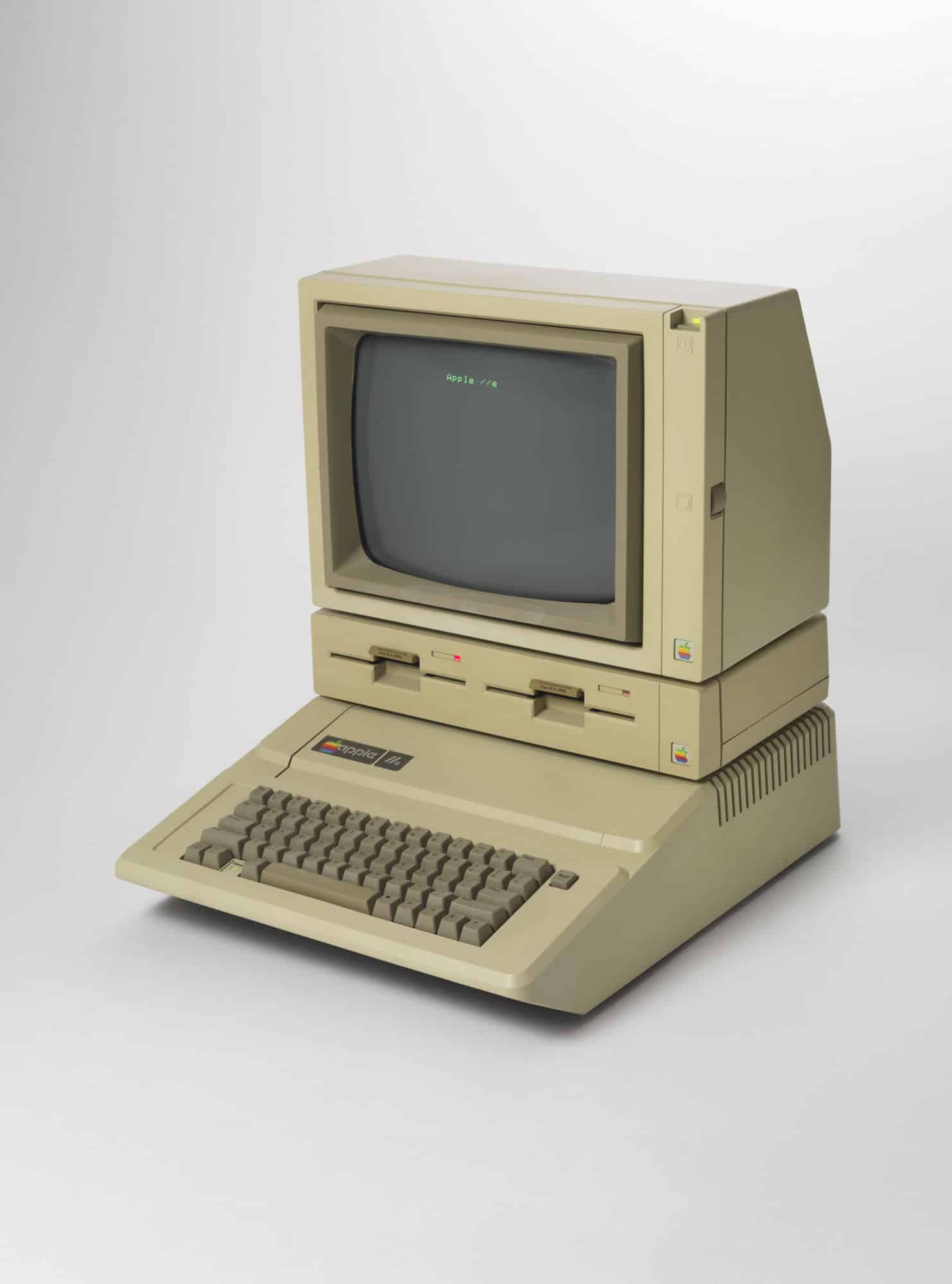

AI is increasingly becoming a part of everybody’s life. Even my mother who previously couldn’t work out how to record Emmerdale on her VHS player is now using predictive text on her smartphone and happy to use Google to get directions without a second thought.

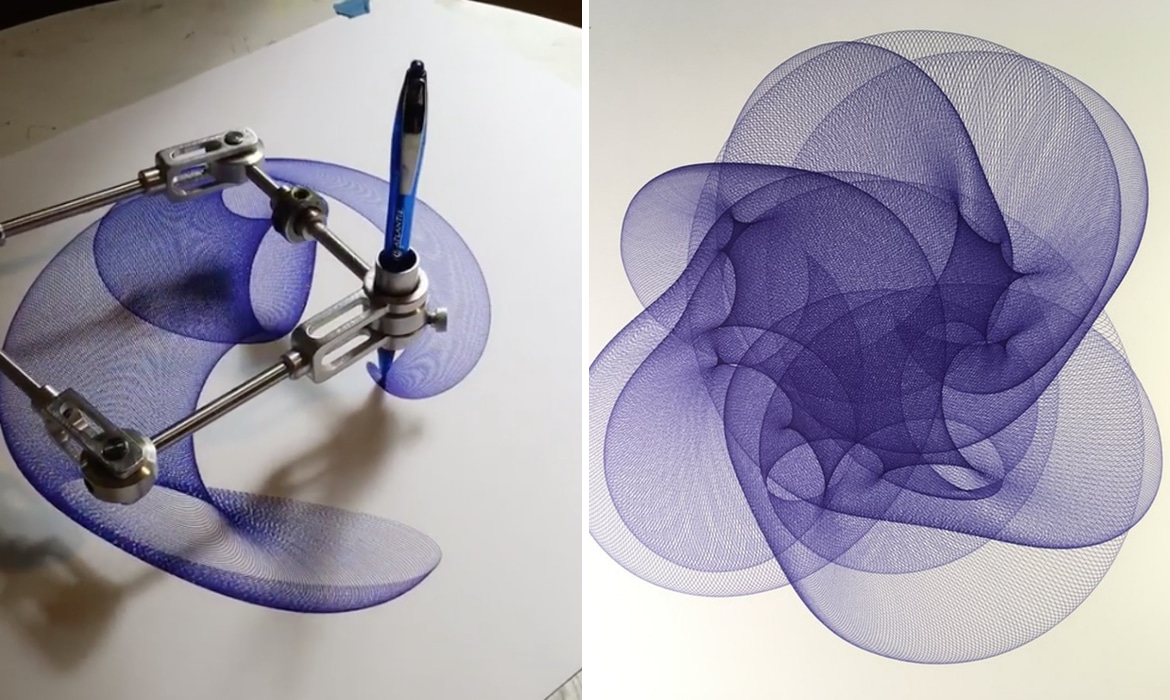

One such area which has proved a source of debate is the use of AI in creative fields; dividing people into two camps. One disturbs creatives that machines are devaluing the creative process; democratising the creation of art to anyone and everyone including machines themselves; reducing the need for professional creatives and potentially putting them out of work. The other camp sees this technology as new possibilities in expression, giving creatives new avenues of discovery; alternative routes to execute their big ideas — maintaining AI is simply a tool like a hammer, camera, or paintbrush, demanding the heart of an artist to pull creativity through.

Below, I will explore whether or not AI is capable of true creativity itself; automated with no human interaction – asking, can artificial intelligence become the artist?

Every creation starts life as an idea, as potential, according to Plato, an ideal we envision which we then strive to realise in the world. Creativity is classically a human phenomenon and appears to be in our nature; not learnt. Looking around at the world today, forests, rivers, mountainscapes and more remain much the same as they have immemorial with the animals inhabiting their homes much the same as they always have, yet we humans inhabit a vastly different world than we did just three decades ago. Though we have virtually the same urges, emotions, and physical capacities, it’s our capacity for creativity that has made us the hyper-transformative species we are – unmatched by any other organism.

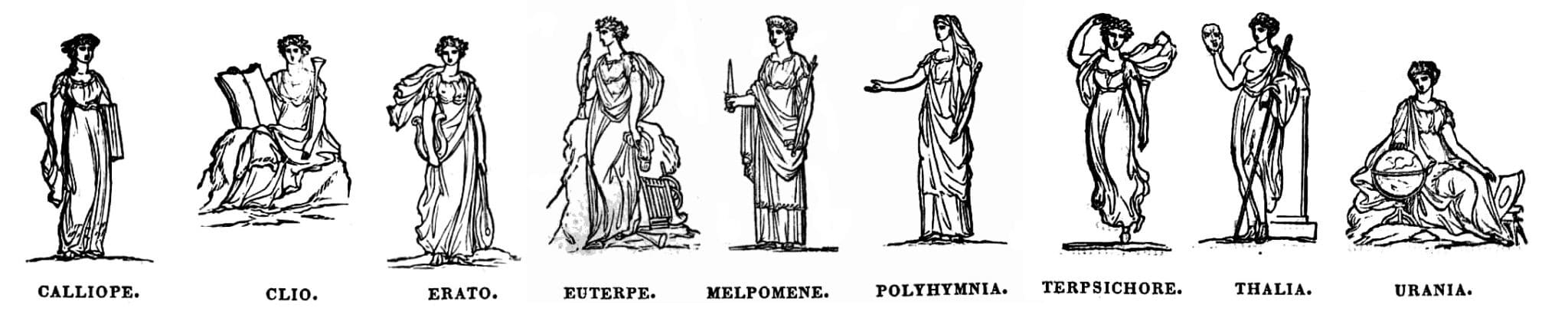

But how do we have these ideas for transformation? The notion of creativity has long been shrouded in mystery. The ancient Greeks believed in the Muses, daughters of Zeus who would whisper ideas down from the heavens to a lucky few. Many working artists boil it down to their intuition, the spontaneity of play or even dreams – regarding it still as an invisible, mystic force for which there’s little way to measure or manage. However, new neuroscience promises to shed better light on just how humans create.

David Eagleman, a neuroscientist at Stanford University and co-author of The Runaway Species (2017), talks about inputs – the more new inputs a brain receives over time, the more creative ideas an individual will have. The brain takes new information from experiencing the world and, in his words, either bends, breaks or blends the data to form new creative links between them – the more disparate the links are, the seemingly more creative the output appears.

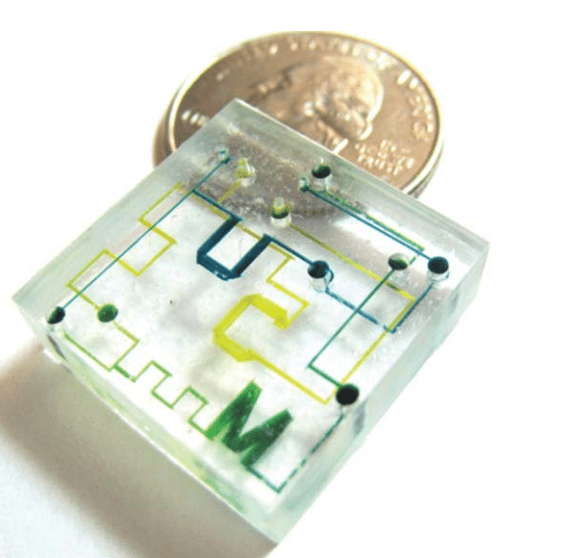

A good example of disparate inputs being connected is nanotechnologist Michelle Khine. Khine made a name for herself innovating a cheap and more accessible way to create microchips by linking the quirky 1970’s arts and crafts product, “Shrinky Dinks”, and applying it to 21st-century nanotechnology. The results made microfluidic chips cheap to make without needing the previously intense infrastructure necessary for processing. The innovation spread quickly across the world where now many labs adopt this new way of making chips – which is essentially building it large and then shrinking it down.

But how does AI have ideas? Margaret A. Boden (1998) writes, there are at least three ways in which AI creates: Producing novel combinations of familiar ideas, exploring the potential of conceptual spaces, and making transformations that enable the generation of previously impossible ideas.

JAPE (Joke Analysis and Production Engine), a 1997 programme that creates jokes, is an example of producing novel combinations with language. The invention of AI doctorate, Kim Binsted, JAPE takes language and makes cheesy puns, stating, “puns use low-level ambiguities to suggest false semantic connections” – the result? Some semi-funny dad jokes.

|

Q: What is the difference between leaves and a car? A: One you brush and rake, the other you rush and brake. |

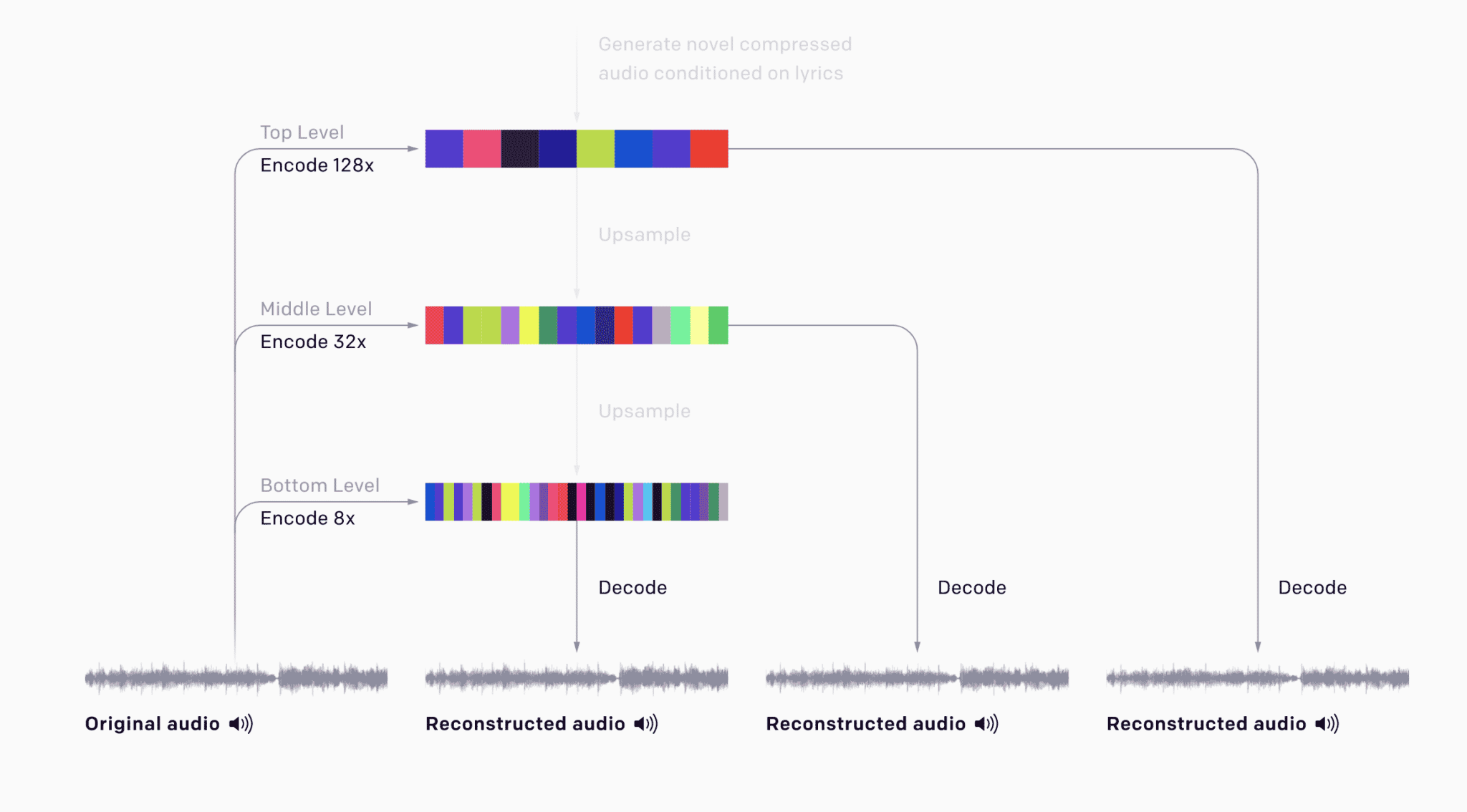

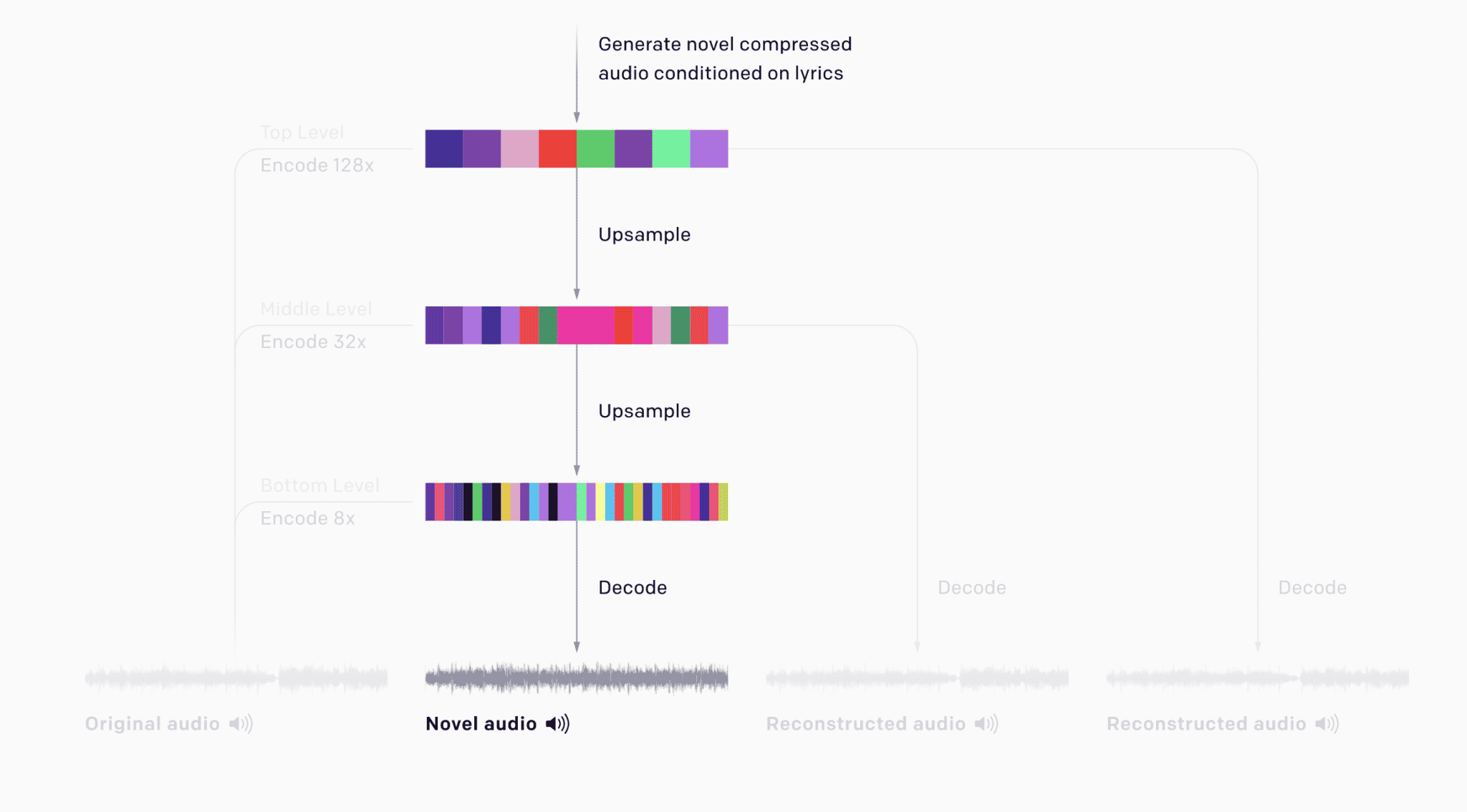

In exploring the potential in conceptual spaces, Jukebox by OpenAI feeds an AI the basics of musical composition while additionally feeding it examples of a specified music artist and genre to have the AI output something in line with those inputs. The results are compelling, to say the least.

“What makes this special is that, given a conceptual space of musical rules and [time] signatures, the computer can find other possible combinations, within this space, that have not been explored yet”

— Arthur Mello

Making transformations, Margaret A. Boden wrote in 1998, has the most potential for “true” AI creativity, prophesying that machines will build upon their own technology; iterating new versions of itself without the need for human intervention. This is what we now call Machine Learning, and over the past ten years has proved a big talking point with the advent of subdomain Deep Learning.

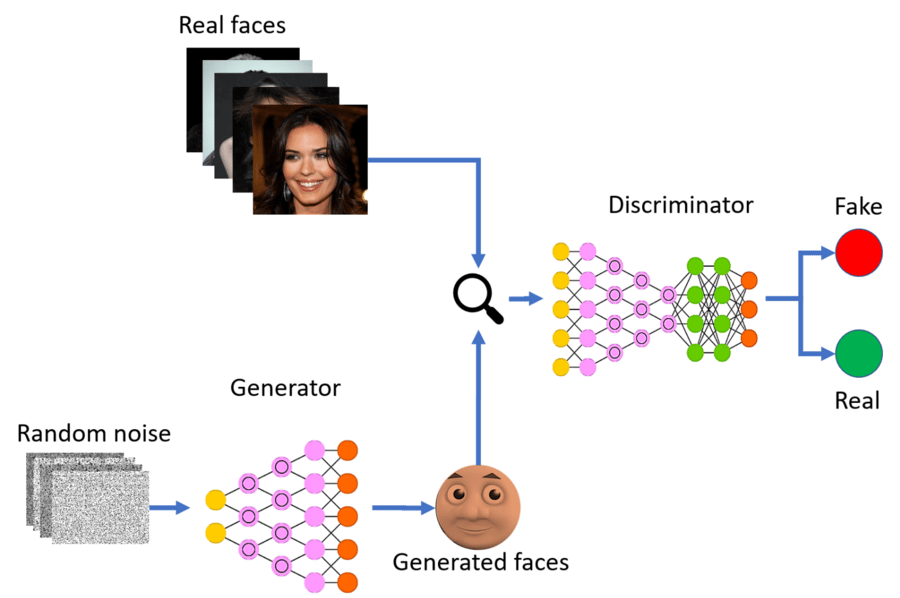

One hurdle for machine learning was AI being aware of what is deemed good and bad. This was so its development could make ‘correct’ decisions and evolve itself to a positive outcome. One way this was achieved was by tracking a user’s actions, storing it as data, comparing this with other users and making an educated prediction on, for example, what folder an incoming email should go into. You can also see this in action with Generative Adversarial Networks or GANs. As a key part of the GAN framework, there is a ‘discriminator’ discerning whether what was just generated is “correct” or “incorrect”, thus outputting the “correct” image generation. It’s protocols like this that enable a model to learn unsupervised, in this example by sourcing a control image to measure and compare the generated image against. Clever.

From the neuroscience of human creativity to the systems that define AI creativity, there are clear parallels between the two. AI mirrors a very similar creative process as we do, taking different data inputs and smashing them together for new outputs. But are the outcomes themselves anything groundbreaking as what has been proven with human creativity across our history?

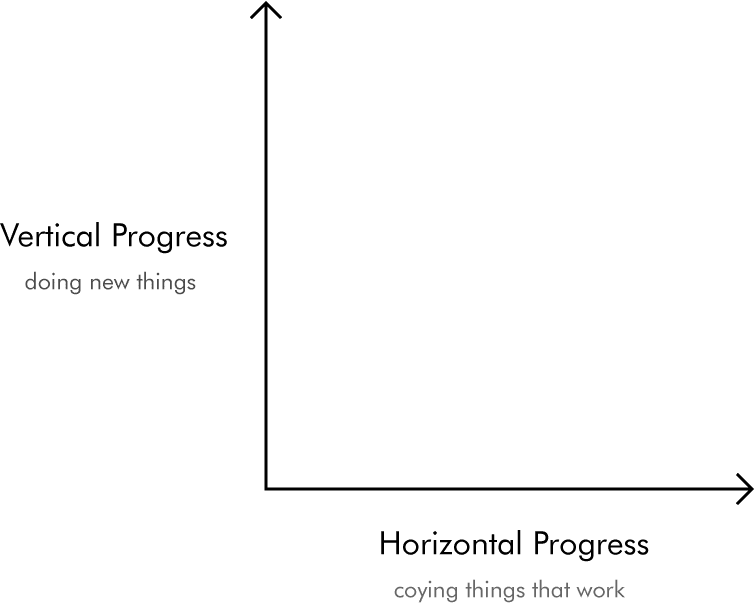

In Zero To One by Peter Theil (2015), Theil compares two forms of progress, horizontal progress and vertical progress. Horizontal means copying things that are already proven to work and applying them to something else of value – taking the value 1 to n. Vertical progress, however, means doing new unexplored things, taking the value 0 to 1 – making nothing into something, what Margaret A. Bowden (1998) calls a domain breaking idea or “big C creativity”.

Horizontal progression is taking a typewriter and making 100 more of them, perhaps distributing them more efficiently, making them more durable, more aesthetically appealing, etc. Vertical progression is taking the typewriter and inventing the word processor – it is singular, it happens once, and the results are new and often strange. In other words, vertical progress is what we collectively call “originality” or “true creativity”.

From this ‘zero to one’ perspective, the question of whether AI is capable of true creativity can be further articulated to whether AI can make the unexpected leaps into new strange territories and offer something new and alien which we discover value in. Can AI make these vertical leaps?

If we wanted to make a new Beethoven-style sonata without the dark arts of conjuring dead musicians, we would feed an AI all the Beethoven sonatas, maybe pepper in some other romantic era composers and, hey presto, we get something pretty convincing out the other end. But to generate an entirely new, never-heard-of-before music genre, we would not only need to feed the AI more than one genre of music but also additional information from other seemingly unrelated places as cognitive scientist Mark Turner writes, “Human thought stretches across vast expanses of time, space, causation, and agency […] Human thought is able to range over all those things, to see connections across them, and to blend them.” This is how wide inputs need to be for vertical or “true” creativity to take place – and even then, there’s a higher probability that the result will be something we’re not quite ready for. This is what makes creativity such a complex puzzle, one which we’ve historically cast the origin to nebulous terms like intuition, genius, or the gods. If generating original and life-changing artworks or business models were as solvable as a Rubik’s Cube we’d have a lot more consistency in domain breaking ideas and a ton more Salvador Dalis and Steve Jobs walking among us. It’s not that the process for creativity is incorrect, it’s that the output by its nature is unexpected, leaving a high probability the output is simply too different or surprising for the culture to resonate with at its time of release.

“[creativity is] a balancing act. On the one hand, our brains try to save energy by predicting away the world; on the other hand, they seek the intoxication of surprise. We don’t want to live in an infinite loop, but we also don’t want to be surprised all the time.”

— David Eagleman (2017)

For “true” creativity in AI to take place with zero human iteration, AI will need to develop large enough networks and continually develop and transform itself in line with an ever-growing landscape of data and apply that data in novel ways until we decide it’s valuable.

But perhaps we’re the ones standing in the way? We’re continually comparing an AI’s output to what other things exist in the world and then iterating the AI to perform more in line with these existing manifestations. Developing AI in this fashion, though impressive and certainly a plug for ‘horizontal progression’ or ‘low-level’ creativity (like 1997’s JAPE), we are not yet seeing an AI output that will have a truly ground-breaking creation from which we can attach words like genius onto. And even if AI did accomplish this, would we recognise it as a product of the AI or a product of the human who built the AI?

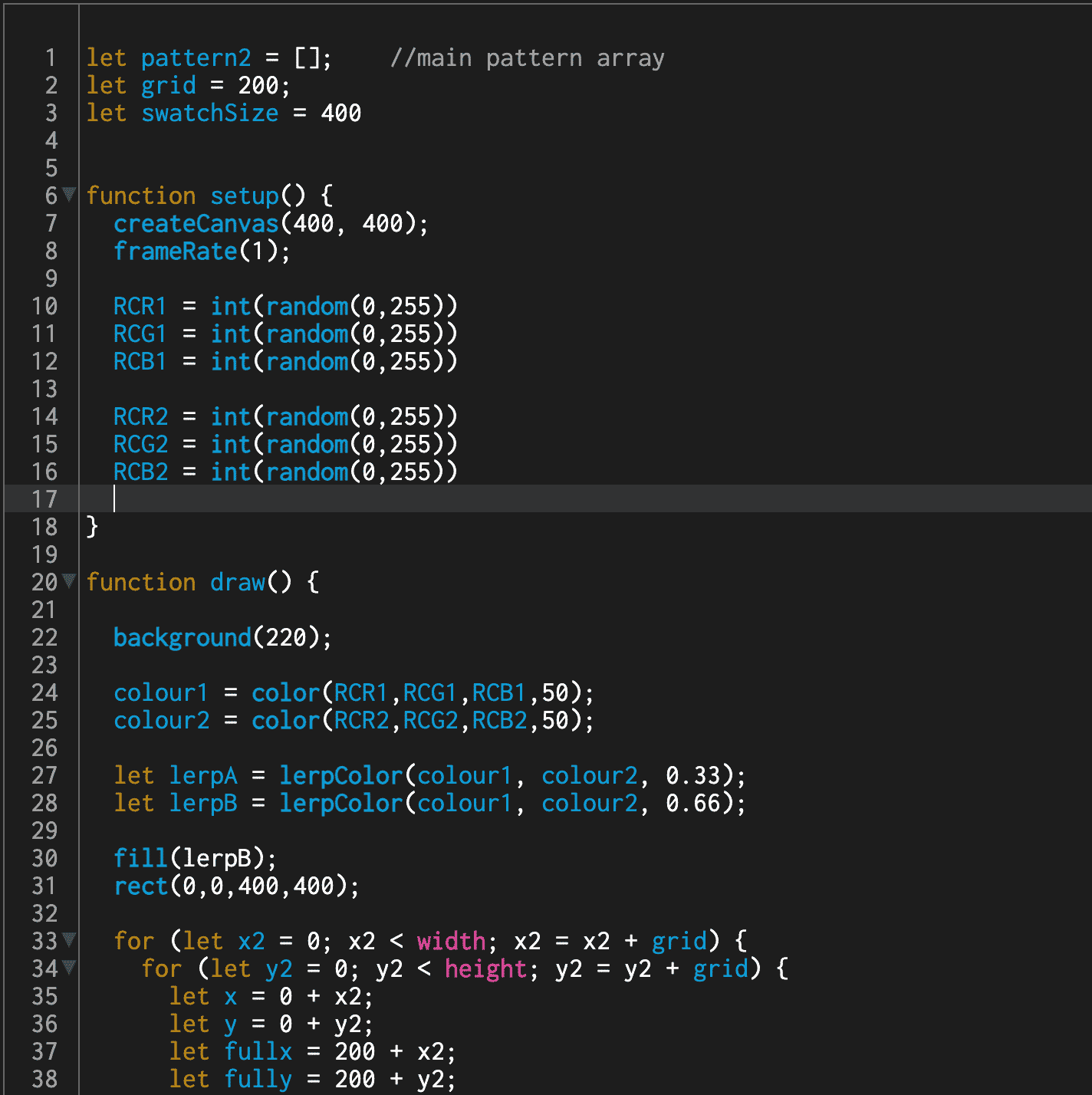

Pattern Machine II: http://tommyhagan.xyz/portfolio_page/pattern-machine-ii/

“The ultimate vindication of AI-creativity would be a program that generated novel ideas which initially perplexed or even repelled us, but which was able to persuade us that they were indeed valuable. We are a very long way from that.”

— Margaret A. Boden (1998)

The best ideas on first public release often disengage and push back the majority; not fully appreciated until long after their influence has been filtered through several other artists or entrepreneurs, making their ideas more palatable or simply better timed for the masses. Van Gogh, now a household name, was hardly regarded in his lifetime. The late-romantic composer Gustav Mahler, although a well-respected conductor of his time, had all his compositions ridiculed and shamed, only to ever see acclaim long after his death. Similarly, Facebook wasn’t the first social media site, there was a slew of other social media businesses with analogous features before it, yet we all chose Facebook to lead. Examples like these are truly endless, the point is if we got to a place where AI did create something of “genius” and displayed “true creativity”, would we recognise it? Would we be influenced by it, or even prop it up long enough for people or machines to build upon toward public adoption?

AI can be capable of “true creativity” as it can take inputs from anywhere and put them together for some kind of new output. Whether the output is good, however, which is to say, the output resonating with our culture – that’s another question. This issue is being reconciled with Machine Learning; having AI teach itself what a respectable output would be and iterating toward that; constraining the possibilities of the output towards something predicted, however, does this give us the necessary amount of “surprise” for it to be declared a fresh new creation?

Right now, the partnership between AI and humans is more well guided, interesting, and creatively productive. The potential for computers to be capable of true creativity and making these disparate connections of data one, is there, along with producing novel combinations of a more linear, horizontal fashion of its own volition, however, whether AI can, on its own, with zero human interference become consistently and prolifically a Picasso, a Mozart, or Elon Musk is still looks far off.