How Do Brands Embody Authenticity? | Part One: The Rise of Authenticity

From the roar of the MGM Lion to the little bluebird of Twitter, from the Peak of the Paramount Pictures’ mountain to the lowercase ‘f’ of Facebook, and from cold grey cubicle built skyscraper corporations to the fun and approachable company culture of Google, there’s no doubt the brands of old would look seriously outdated if they came out today. But what is it that’s outdated? Do we no longer like lions or mountains? The change lies in our need to buy off real people. We are on the search for authenticity. But what is an authentic business? And what does it mean to be authentic?

“I Taut I Taw A Puddy-Tat?”

i. Globalisation

Today, almost everything we touch in our supermarkets comes from across the globe. An ordinary weekly shop at a local supermarket touches roughly five continents, with melons coming from Asia, strawberries arriving from Spain and locally caught UK fish processed in China before being sent back to be sold in the UK. It seems the sort of lavish lifestyle reserved for the Kardashians, but it’s not, it’s ours, and we hardly know about it.

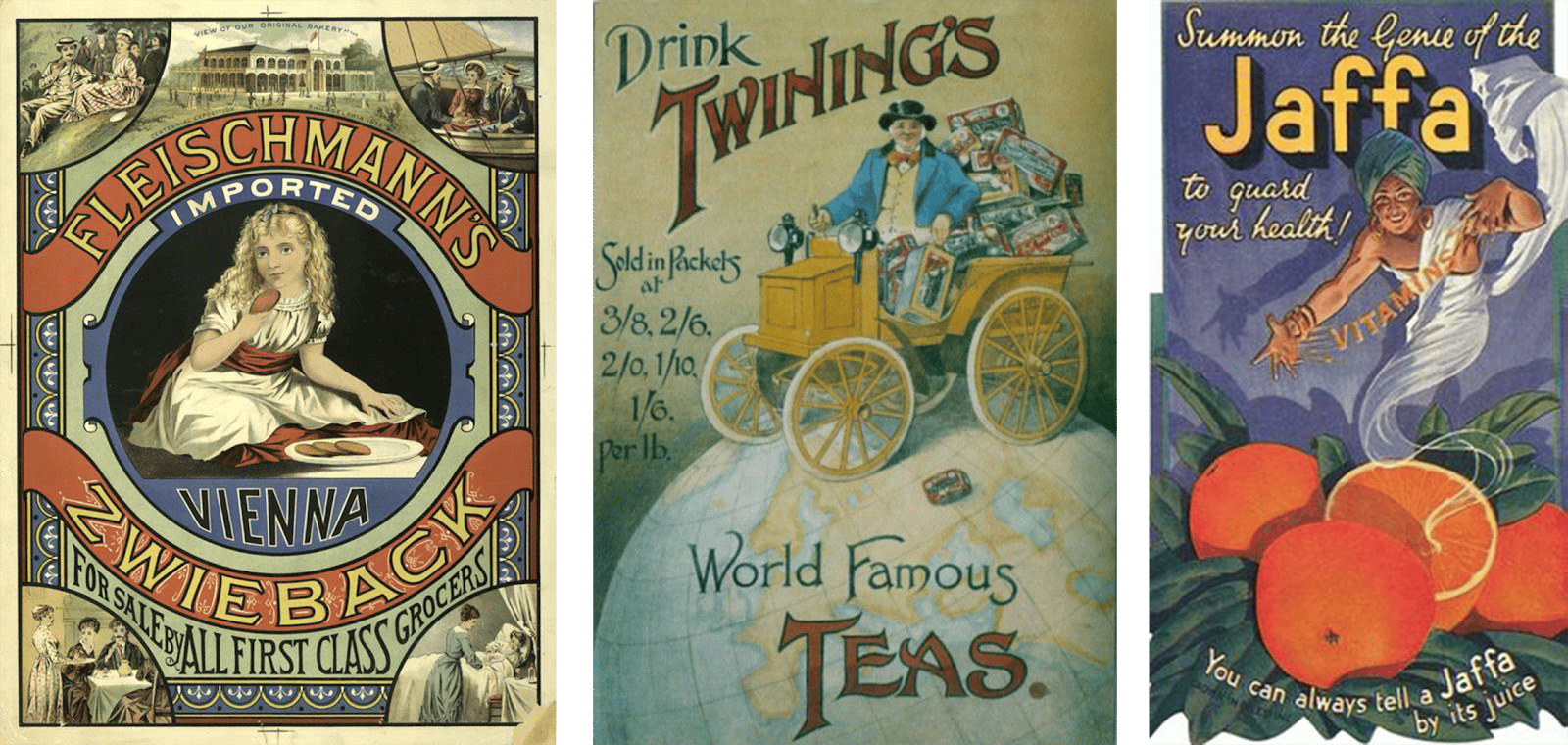

In the Victorian era, Oranges from Italy and Spain used to be considered an extreme luxury, nowadays, we pay a high price to have our Apples hand-picked in Kent. What used to be considered a luxury has now become the norm, what common folk used to settle for are now being sought for by the wealthy.

It makes oranges look like a ride at a theme park. A spectacle to behold.

We can understand through the principle of bulk processing that shipping things across all corners of the globe are now cheaper than before. For example, Scotland’s minimum wage is about four times than China’s, which explains why Scottish fish is often processed in China before being shipped back to be sold in Scotland. But what is it about the hand-picked apples from Kent? Why are these now being sought for with a higher price tag and a higher social status attached?

Wally Olins claims in his book ‘Brand New’, “Authenticity means provenance.” Olins’ case is that as businesses have become more global, we have prized the local, meaning, as a brand becomes larger and larger, we perceive that brand moving further and further away from their origins and thus our inner values as individuals. This, alludes Olins, makes room for small entrepreneurial businesses to move in with more personable, approachable, and non-corporate branding which gains trust in the consumer. It’s not necessarily because the brand is local it is trusted (though that can help), it’s because it doesn’t appear to belong to a global conglomerate, it’s the anti-globalisation we like, not the fact we can pronounce the location easier.

Askinosie is a chocolate manufacturer importing their own beans and working predominantly in South America and Asia, proving hardly local to their target markets in western territories. Yet for them, they appear ‘local’ because of the ethical values and actions they are making which we are excited to relate to. During one of their sourcing trips in the Philippines, they discovered a problem at the village’s Malagos Elementary School—many students were suffering from malnutrition. In an effort to fix this, Askinosie began a sustainable nutrition program shipping and selling Philippine hot chocolate to America where 100% of the sales provided meals for the students at Malagos.

The shadow of this is the chocolate giants Nestlé. It’s hard to demonise the brown velvety beauty of chocolate but Nestlé managed it when it was discovered their chocolate was being made by 12 to 15 years old in slavery-like conditions. Seeing the duality of these two brands and the and the uproar Nestlé produced at the time, we can see the new consumer needs of the 21st century.

I always secretly believed chocolate could bring the world together.

ii. Cultural Scepticism

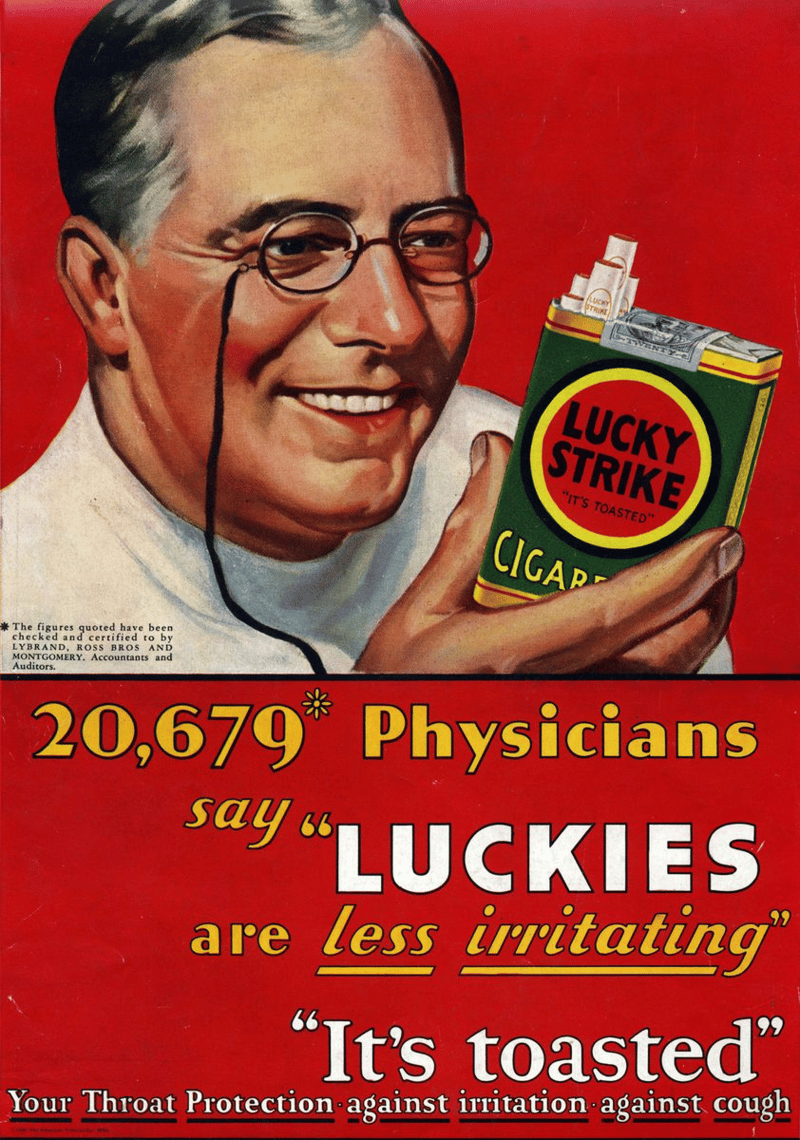

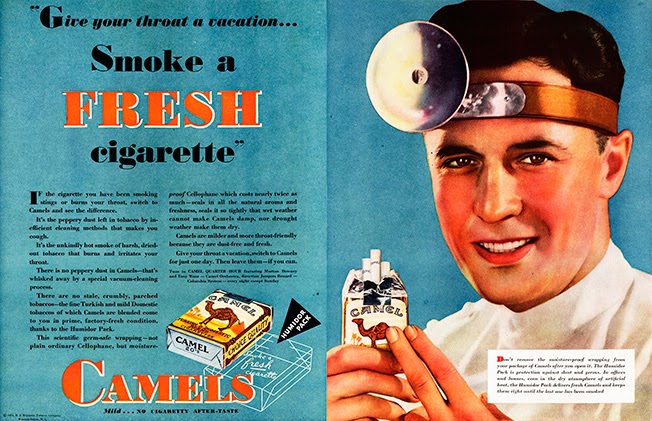

It seems hard to believe now but there was once a time when we respected and trusted our corporations and political leaders. John Musgrave a Vietnam war veteran solemnly remembers, “we were probably the last kids of any generation that actually believed that our government would never lie to us”. In the 1950s, to get around the scientific evidence of smoking is bad for you, admen just promoted smoking as healthy instead, assuming, we’d just blindly go along with it – and for the most part, we did.

Because doctors always know best ; )

As we moved through the 1970s and into the 1980’s we saw presidents and prime ministers continuing to put their countries into wars like Vietnam and the Falklands with little clarity to why. Protesting the government became a common counterculture occurrence, scenes of police brutality were televised nationally, and it turned out smoking was bad for you – imagine that. Moreover, making this scepticism toward power have some sort of intellectual clout rather than just belonging to paranoiacs with an axe to grind, thinkers like Foucault and Derrida along with other postmodern thinkers offered an appealing scepticism about our commitments to these meta-narratives; having a strong appeal to the privileged intelligentsia of western democracies and giving them the tools to deconstruct positions of power from the safety of their universities.

Today, any promise given to us by a powerfully positioned brand is met with pondering scepticism. Today, brands are less and less able to rely on flashy ‘As Seen On TV’ stickers to instil trust in their consumers, products and services now have to be remarkable in some way to get our attention (salted caramel KitKat), and once they do, they have to answer our burgeoning scepticism so we can understand that they’re on our side (it’s part of our Cocoa Plan…).

iii. New Social Power

The people drive the marketplace. By choosing what to buy, we have the power to vote for what is good and what is bad — what stays on the shelves and what is removed. Today, we shirk at the idea of giving money to companies who have less than ideal ethics, more than ever we are aware of our consumer power. With the free and visible flow of information on the internet, most of a seller’s behaviours are laid bare. Now, we not only have the power to vote with our money, but we also have the power to choose between a gleaming five-star review or a scathing 1-star.

As of writing this, YouTube review channel ‘Unbox Therapy’ accumulates 16.7 million subscribers, where another, ‘FunToys Collector Disney Toys Reviews’ accumulates 11.5 million – we are captivated by reviews, whether that’s reading them, watching them, or giving them ourselves. It could be leaving a review for a £2.99 USB charging cable from Amazon, a review of your general manager on Glassdoor, dissecting the prime minister’s last speech on Twitter, or a less than pleasant Uber driver you had last weekend. We now potentially have more power to change the culture than ever before, trust has become a sought after commodity and businesses have started learning how to gain our trust by apparently being more authentic.

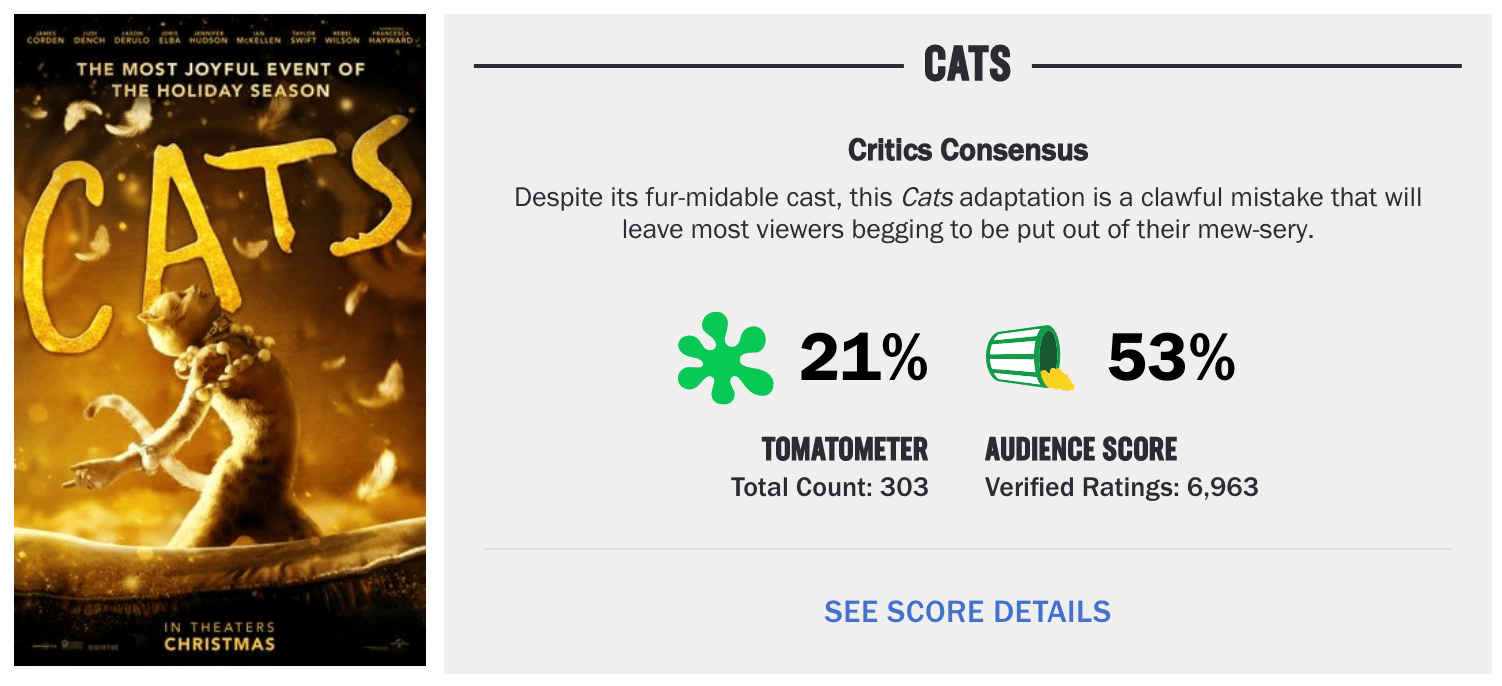

It’s “The Most Joyful Event of the Holiday Season”… apparently