Is Seeing Believing?

The Pillars of the Parthenon aren’t actually straight…

The NeXTcube wasn’t a perfect cube…

And the letters I type aren’t all dead flat to the baseline…

Every day, perceptive illusions are built around us because sometimes when something is constructed ‘perfectly’ it doesn’t look perfect. If the Parthenon’s columns where perfectly straight, it would not look straight. If the NeXTcube was a perfect cube, it wouldn’t look like a like perfect cube. And if ‘o’s, ‘e’s, and ‘a’s, etc, were all aligned perfectly to the baseline, it would feel like the letters weren’t even.

The point is that we don’t actually see with our eyes but rather, with our brains.

If you imagine the eyes as a portal for light to be interpreted by the brain, the brain can make all sorts of conclusions on what’s coming in.

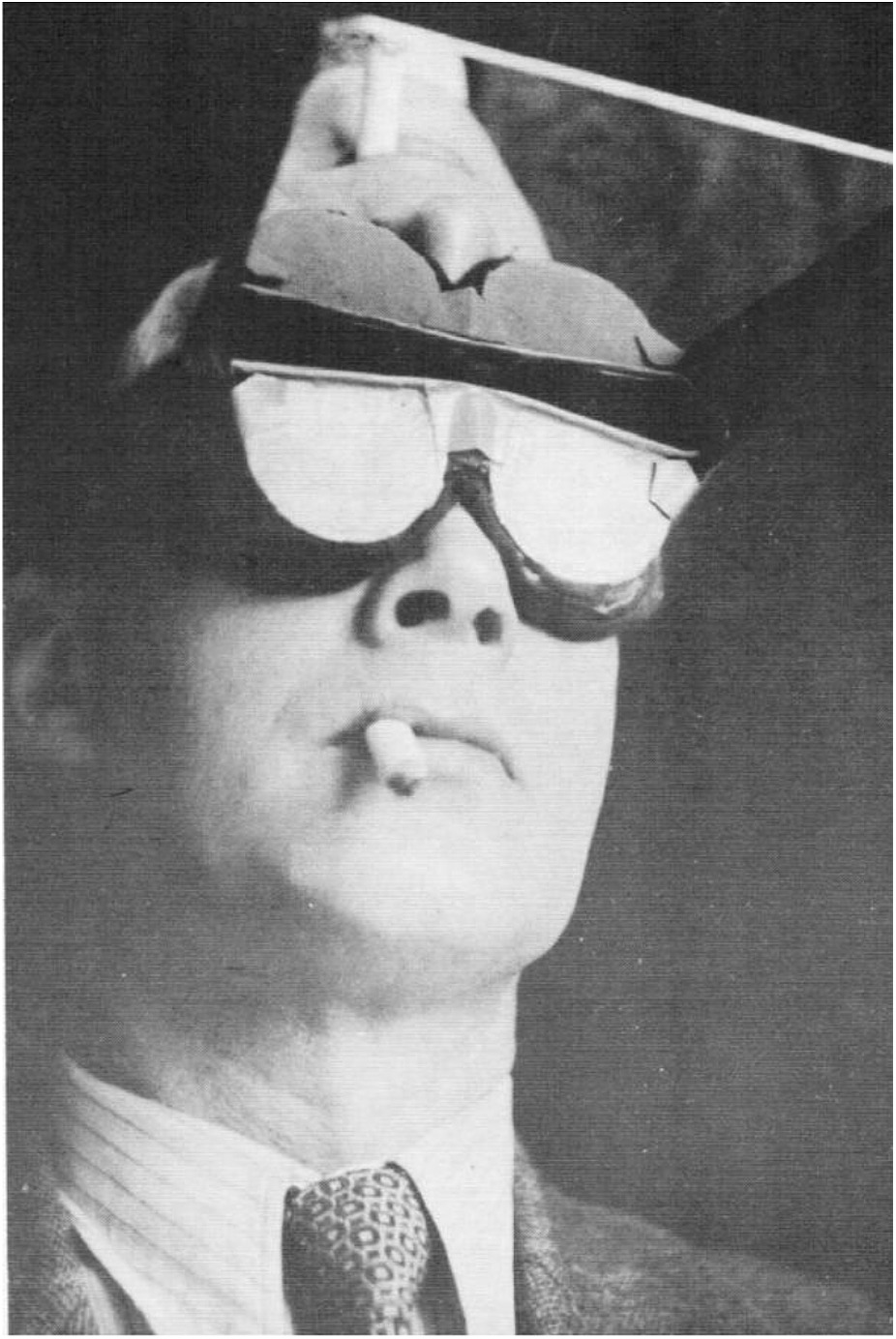

The Innsbruck Goggle Experiments of Theodor Erismann (1883-1961) and Ivo Kohler (1915-1985) was a study where a subject had special glasses made that would flip his vision of the world upside down. After a few days stumbling into table tops and stubbing each one of his toes, his vision flipped to the “correct”, or common way of seeing the world – still with the topsy-turvey glasses on.

Legend

Much of the way we see is a survival mechanism honed from hundreds and thousands of years of evolution. The colours which are most vibrant to us tend to be the poisonous berries in the forest, and sharp, jagged objects aren’t as naturally attractive to us as softer, rounder objects. So when continually confused by an upside-down visual stimulus, the brain instinctively and flipped it back for him. Cheers, Brain!

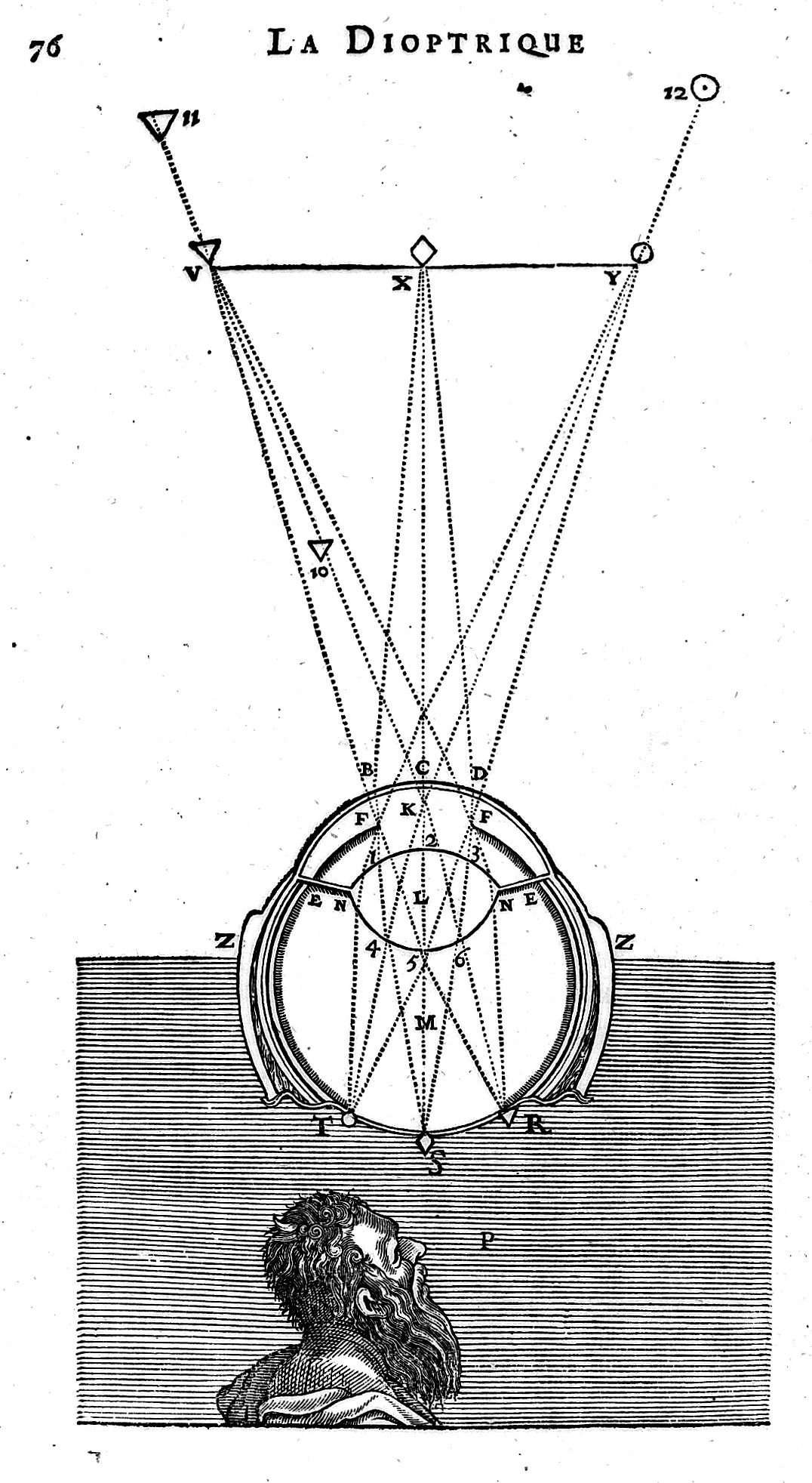

A very early and influential depiction of the eye gestured toward this very idea. The philosopher and natural scientist, René Descartes, famous for his existential quote, “I think, therefore I am” (1637), was obsessed testing whether our perception of the world was indeed the real world. In this diagram, he showed light entering the lens of the eye on and converging on the retina and travelling to the back of the eye.

However, he notes, this is not yet seeing. The image would then have to be interpreted, which Descartes called the sense of judgment. In fact, Descartes drew a picture of a judge to playfully symbolise this.

Descartes, 'Vision', from La Dioptrique – Wellcome Library, London

Of course, at this point in history, the depiction of a judge making sense of the image is merely scratching the surface of the real beast behind the eyes; sorting and bringing the confusion of light vibrations to a common and clear understanding.

Seeing The Brain

Today, with advances in science we have the ability to effectively “look” into the brain and see the activity. Through this, we can understand with the help of fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scans that the brain has localised activities. From this, we can see that it’s not the entire brain lighting up every time it’s stimulated, but specific and specialised areas. And “seeing” alone lights up a total of seven independent areas with a total of 305 connections.

This tells us that even though the image first lights up just one area of the brain, it then extends onward to connect out to many more locations. And not only that, but it happens in a series of rapid back-and-forth exchanges – like a computer.

Fellen and Van Essen, 'Hierarchy of Visual Areas'

This, above, is the most conclusive mapping of the brain’s visual programming. As we can see, like a computer, the pathways prove distinct but are processed in parallel. From here, we can see that vision isn’t just a matter of light entering the brain and it being ‘judged’ or ‘made sense of’, it’s a vibrant display of a back-and-forth jitterbug across seven locations in the brain.

On a deeper level, the parallel is that this image above is rather a ‘computation’ of a real image, and is now being fed through light into your retina which will then be processed in a similar fashion inside your brain. Meaning, the systems we’ve created for displaying images have unknowingly been replicating the system present inside our own skulls.

Beyond The Brain

If the job of the brain is to make sense of all this complex information and produce something clear and definite, what happens when we feed our eyes a blurred, or hazy image?

Early photographers, like Julia Margaret Cameron, demanded to know in a letter form 1864, ‘What Is Focus?’, “Do we concentrate on ensuring that the piece has sharp lines rather than giving viewers a poetic insight into the subject of the photograph?”

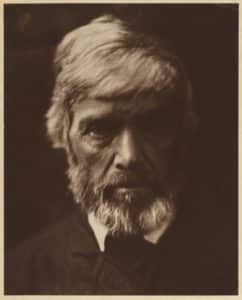

Thomas Carlyle – Julia Margaret Cameron

This portrait of Thomas Carlyle, for example, is arguably a more realistic portrait to portray the historian’s personality as a ‘seer’ and a ‘mystic’ than a crisp, detailed, more contrived photo would have conveyed.

When we stop and absorb the evolution of JWM Turner’s paintings, our brain figures a different message using the information present on the canvas. As we scroll through each piece we can sense the reach for the expression of pure sensation, sometimes almost leaving the world representational art completely and entering into abstraction.

As we enter a world where our brains have to stretch to bring things into coherence, we start pushing outward toward the edges of our understanding. The 20th-century philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein, writes, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” (Tractatus Logico-Philisophicus)

Meaning, what we fail to make sense of and put into the linear constructs of language are beyond the limits of our common understanding – or ‘existence’. As we approach something which presents problems for our minds to “solve”, we are pushed out into a sensation of “transcendence”.

Meditation techniques give us a pure and fast way to enter this world of ‘non-existence’ so we can achieve a profound peace and sublimity outside the constant mechanics and ‘computations’ of our mind. The feeling of love can not be put into words, a starry lit sky leaves us speechless, and music can bring us to a teary ecstasy, these are all examples of where the mind leaves us with a pure, thick beauty coming from within – this is universal to everyone at some point during their life’s experience, but as soon as we try to speak, explain, and define this feeling, the moment leaves us and the transcendence fades, leaving us just with a scramble of words which aren’t worth anything in comparison.

In music, as we move from Classical into Romanticism, and from Romanticism into Modernism, music becomes more dissonant, exotic, the timings looser, and the structures more ambiguous. This makes the most common chord in Jazz, a major seventh, sound unbearably dissonant to a Baroque composer. But much like the blur of nature present in a Claude Monet painting, the dissonance is a compelling a source of emotion and feeling – to those who know how to ‘feel’ it.

By the time we reach the atonal music of Arnold Schoenberg in the 20th century, the musical language pushes our brains so far we can’t establish any common sense of it – the limits of our language define the boundaries to our existence and this is beyond which our brains are capable of cleanly interpreting. Here, in the world of Schoenberg’s ’12-tone serialism’, we can no longer make sense of the auditory phenomenon which is music – this can be underpinned in the fourth movement of Schoenberg’s String Quartet No. 2, with the words: “Ich fühle luft von anderem planeten” – “I feel air from another planet”.

A similar thing happens with the visual abstractions found in the works of Kandinsky, Franz Kline, or Jackson Pollock. To read abstraction this far from representation one must feel, not analyse, not ponder or think, but just be with it. It is a meditation. A practice in transcendence and living now, where all the universe unfolds.

On White II – Wassily Kandinsky

Is seeing believing? Well, we know vision plays a huge role in the brain for survival but it also proves a portal into sensation and feeling which helps us make sense of the world on a more philosophical and poetic level. From the outside world around us to what happens in the brain and what happens beyond thought – It’s all one big hodgepodge of existence that is certainly fun to experience. But I’d say, for me, ‘feeling’ is more believing than simply just ‘seeing’.

The Rothko Chapel, Texas

For more to read on this:

Here’s that study on the “topsey-turvey glasses”: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28521154

You read the full Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus by Ludwig Wittgenstein right here: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5740/5740-pdf.pdf

And lots and lots of this information was inspired by the writings of Nicholas Mirzoeff in ‘How to See the World’ which you can find here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/How-See-World-Nicholas-Mirzoeff/